Appeared in CCNY’s OBSERVATION POST (12.4.72)

An Introduction to the article:

My father, became a member of the Directors’ Guild, and of the entertainment business’s Friars Club, but his entire professional life was spent as a television commercials producer, and as a publicity writer in the movie business. Though these jobs did not allow for him to develop his more creative talents, they did develop his understanding and love for great talent, as even in the depths of the “generation gap” of the ‘60s, when styles in every aspect of our culture radically changed, when the hippest man in the room had been Frank, Dino and Sami, all of a sudden Dylan, the Beatles and Jimi Hendrix could be singing, “Something is happening here, but you don’t know what it is, Do you, Mr. Jones?”

Al hated the “messiness” of the beatnik and hippy style, and even of the Knicks young sixth man, Phil Jackson, but he appreciated the song-writing of Dylan, the harmonies of the Beatles, the singing of Janis, and the guitar playing of Jimi.

And through Al’s influence I swung with Sinatra, Ella, and Judy.

In the political realm, I took personally the savage, criminal horror of napalming women and children in Vietnam, and was traumatised by the assassinations and the traitorous cover-ups of why they were killed. Al and I would have voted similarly, though he likely found Bella Abzug too messy, and might have chosen Ramsey Clark or Pat Moynihan instead. But we found common ground with Peter Hamill, Allard Lowenstein and Jack Newfield.

I had read and was greatly moved by Newfield’s book, a personal portrait of his friend, as I read, ROBERT KENNEDY: A Memoir.

It deepened my understanding of the tragedy, to learn of the emotional struggles the grieving brother suffered to answer the perilous call to fulfil his brother’s mission, and to end the horror in Vietnam; a tragedy made plain with the election of Richard Nixon.

So, my father and I would share articles by and about Lowenstein, when he insisted that someone had to challenge Johnson over Vietnam, to save the soul of the Democratic Party, or articles by Hamill or Newfield, pointing out hypocrisy, corruption or the crimes of politicians or NYC slumlords. And we shared those articles with my father’s mother, a lifelong Republican. It is one of my proudest family moments that, Eva finally saw through Nixon and his administration, saying, “They are liars and murderers, voting for George McGovern, the anti-war liberal and successor to Robert Kennedy, in 1972.

So, when I joined the student newspaper at City College, I thought to interview Newfield, and he agreed.

Jack Newfield: A Working Class Hero

When political discussions come up, I’m the type of person who will invariably grown more and more pessimistic about poverty in the midst of wealth, the disgraceful war in Vietnam or the outrageous corruption in government. I finally end with a cry of hopelessness because Mr. Average American doesn’t seem to understand anything except fear of Blacks.

A few years ago I thought I was pretty clever to know that the inhuman conditions in the jails would soon become a major political issue; just as I’d known woman’s liberation would be too. When I heard that there was nothing being done about the Ghetto babies who were being poisoned by lead paint peeling off tenement walls I was angry, but it also confirmed to my idea that no one seems to care about anything that doesn’t directly affect them.

And now, evidence that Judgeships are being boughtand sold confirms my fear that it will be impossible to make things better in this country through traditional political channels. These are the days of the Godfather, not St. George.

While most of us were wallowing in the mud of Nixon’s America, and as we cry in our beers over “Four More Years,” Jack Newfield kept the jail issue alive in New York when it would have died as people forgot Attica, made us aware of lead poisoning in paint, and is now leading the drive to get rid of judges on the take.

Anyone who doesn’t care about the suffering and frustration other people have to live under won’t give a damn about his work, but for those of us who are concerned it has a very real sorrow and pity. I’m painfully aware that, this world is one in which children suffer. Jack Newfield is one person who has the “hubris” to act to lessen the number of suffering children.

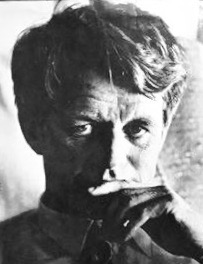

Being late, I ran ten blocks to his office at the Village Voice. “He’s late. Jack’s talking to an old friend at home”, a young man who serves as the fourth floor receptionist, secretary, and administrative assistant informed me.

“I have set up my tape recorder. Can I go in his office?” He laughed.

“Sure.” He led me to Jack’s “office,” which was five feet by seven feet. His desk looked as thought it had been bought second hand on Canal Street for twenty dollars. It had two filing drawers which were uselessly small. Papers covered the surface of the desk twenty layers thick, trailing off the edge, on to the floor, and across the room. An old style typewriter, which jack Newfield says is never used, lay in the path of the papers, looking as though it had been there for months, perhaps moved from side to side by whoever cleans the place, if anyone does. Jack’s memos for the day are simply placed on top of the everything else. He had no trouble finding them as he entered the cubical.

“Hello?” said Jack Newfield as he approached his office, sensing someone’s presence in his home away from home.

I was caught in the act of recording my description of his meagre office and was feeling guilty about my allusion to the cost of his desk.

“Oh! Hello, I’m David Mendelsohn,” as I shyly stuck out my hand.

He looks more like Robert Wagner, the politician, than Robert Wagner, the actor. I could not classify his style of dress except to say that it doesn’t seem to be important to him, and that probably each piece of clothing is chosen on its own, aside from how it will go with everything else chosen for the day. His striped shirt is open under a dark plaid, wool jacket. Although there is still some youth in his face, at 35 Jack Newfield’s eyes appear to have aged under the weight of having to witness the defeat and burial of a few too many good men and sensible ideas he had hoped to see to fruition.

As his leathery bottom lip dropped down further than usual towards the memos he was reading, I was building self-confidence by reading over the questions I had prepared.

My interview began with him asking me about my New Journalism class. “Are there any girls in the class this year? When I spoke last year there were none. It seems New Journalism is a male phenomenon.”

I mumbled back something about “Yes there are two, and they write about Women’s Lib and sexual encounters.” I hadn’t thought of them as women before, or rather as female New Journalists, just fellow classmates.

Fumbling with my notes, hoping to find a question to ask in order to stay on top of things, I blurted out the first one on my list.

“I know you’ve been investigating judges, and as I see it, you’ve proven that a few of them are outright salaried employees of the Mafia, but what will come of your work? Can a few muckrakers cause any real changes?”

“Well, for one thing, one of those judges is already being questioned by the higher courts. You see, you’re right, any politician or bureaucrat can make it through a week’s bad publicity, but when they know you’re going to keep coming back, and coming back, like Joe Frazier, then something will happen. We got Lindsay to finally fire McGrath. If they know you’re gonna get on TV and radio, lecture in Colleges, and work until you’ve created a constituency, then something happens. A couple of mayoral candidates are using judicial reform as an issue. Nader is a muckraker, and so is Jack Anderson. So I’d say all of us together are causing some changes.”

We were interrupted by a phone call from a woman with a story about a corrupt judge.

“Everyone knows a judge who’s doing something under the table and they call me up. People understand that something is wrong, and they’re willing to help. It doesn’t take an intellectual to see that if the guys are taking fixes to let heroin dealers go, then that is making a contribution to street crime.”

His apparent faith in the people launched me in to my next question. “Why did McGovern lose? I think he lost because everyone saw the convention and associated him with the freaks, blacks, longhairs, women’s lib, gay lib…”

“Yes, but it is understandable that they should fear these people. McGovern had the quota system for them but not for old people, poor people or the Irish, and Italians who voted for Nixon. Look, Nixon was the incumbent, he was a known quantity, and McGovern kept changing his mind. People haven’t always agreed with the Kennedys but they do feel they know where they stand with them. Not McGovern, and anyway, it seemed that the war was over. Nixon wen to China and Russia, the stock market was up. There’s no great swing to the right. More liberals were elected, and Kennedy leads Agnew by seven points in the polls.”

The subject of McGovern brought back all the hope I’d had that maybe, just maybe, he could be elected, that America would finally see what a liar Nixon is and how good and honest a man McGovern was. I’d then be relieved of having to see more pictures of napalmed people. “Throughout the campaign Ron Rosenbaum was writing stories for the Voice which gave his personal view of McGovern, and it wasn’t flattering. I wish he wrote pieces to get more votes not fewer.”

“It’s not the job of the journalist to be a propagandist. I did a critical article on McGovern at the Convention. The first responsibility is to tell the truth. If you’re going to propagandize then you go in to his government, and end up like Schlesinger and Sorenson. This is no time for people to have illusions. Tell them the truth… also you’d lose your credibility if all you say about McGovern is that he is a saint and a hero and a savior just because he’s much better than Nixon.”

He was right about that but when he put down the left elitist disinterest in the hard life of the lower middle class I realized I had never really cared to listen to them through their Bunkeresque style and academic ignorance. Newfield made me feel for the working stiff who makes $6,200 a year, comes home tired every night and hears that McGovern has a plan where welfare families get $6,500 for doing nothing. That’s not to say that they shouldn’t get it but for once I wasn’t overlooking their outrage completely. He also thinks liberals have been wrong in missing the importance of violent crime as a genuine issue.

I was left with little to love about McGovern except my belief that the ex-minister would have done as promised, and pulled us out of the war. I asked my next question with trepidation, fearing that I was a fool, not those average Americans who were so traumatized by ten years of politicians’ likes about the war that they didn’t believe anyone could have us out in ninety days.

“Do you think there was no chance, that if elected, McGovern would have had us out of Vietnam immediately?”

“Yes, he would have done that.” Aah, at least he would have been our savior there. I was relieved that Newfield’s perception of Lonesome George’s sorrow over the war conformed to mine.

“McGovern would have been a good liberal President,” he went on, “but like Lindsay, he’s a fuck up.They both, unfortunately, give good intentions a bad name.”

Jack Newfield was the sports reporter for the Hunter College newspaper. Then he went to Mississippi as a civil rights worker. Afterwards sports no longer seemed a serious enough subject. He believes in writing about what you know best, so when he started being more of an activist than a ballplayer that is what he wrote about.

“Why did you get involved? Was it because you reacted emotionally when you saw these people were being fucked over and so you wanted to help? Or was it more of an intellectual decision? I mean, do you see right and wrong in the world and feel that you should do what you can to make the good win out?”

“Yes, I suppose there is a moralism involved.”

“Why is it that nobody gives a damn about poor people and you do?”

He answered quickly. “I grew up poor. My family is poor.”

At once I was no longer doing an interview with a “famous man,” who had sophisticated ideas. Jack Newfield was all of a sudden very real to me. It struck me that here was an integrated being, who simply did his work because it came naturally out of his past and present experience.

“What makes anyone left-wing? I think it’s a moral outrage over injustice.”

“Yes,” I said, “but for me, I was always middle-class…”

“But you’re literate” which somehow didn’t explain my being left-wing to me. At times I waver and then give up the hope that politics will be my answer. My moral outrage perhaps stems from guilt about my privileged position, and so is off again on again, whereas his is a constant low-grade, but concrete reaction to a lifetime of both reading about injustice, and more importantly living through it. His family is poor so he has no doubts about what he’s doing.

The hypocrisy of some Liberal do-gooders who talk about things in the abstract and who get self-righteous disturbs him. “Lindsay shouldn’t tell people who are earning $5,000 a year to send their children to integrated schools when he sends his to private school. The same goes for journalists. You should have experienced what you’re writing about.”

“What kind of art do you like?” This was one of my off-beat questions designed to get to the real person.

He didn’t understand exactly what I was looking for, “Well I enjoy music … Dylan, the Band.”

“How about painting, sculpture?”

“No…not at all. Photography, realistic photography.”

That made sense to me. “Do you ever go to an art gallery?”

“No I don’t…that’s a good question.” No, he wouldn’t go for the nihilistic abstract sophistications of modern art which I enjoy. No, realistic photography. Concrete images of a real world.

So I tried another “insight” question. “Do you write poetry?”

That one drew an audible chuckle. Of course he didn’t write poetry, not with a whole world out there in which to act. He wouldn’t be attracted to pushing around and dwelling on personal anxieties.

Last weekend I was visiting my parents, who were entertaining about fifteen people. Among them was a man who I’d always thought to be a pretty decent guy. As we talked he revealed some ideas that were so silly to me I couldn’t become angry even though they were contrary to my beliefs. He actually subscribes to the theory that blacks are genetically inferior, and that the lack of industrialization of Africa is proof of it. But whatsmore, he and those who agree with him, which he often reminded me is most of America, are “preparing to fight if it comes to that.” When I left the party he was especially warm and friendly.

Although I had made very clear my reasons for thinking his views barbaric and absurd there was an understanding on both sides that our philosophies would not change so why not get along on other matters. However, the problem remains that our society suffers from racism, and are a people “following orders.” They proved that by re-electing Nixon.

I’m sure Newfield could talk the language of this man. He feels the impotence of the white who owns his half of a 19,000 dollar two family house which is “threatened” by a changing neighbourhood. Perhaps he could get through to them that the problem is not the blacks, but rather a system out of everyone’s control, except for a few who are rich. Certainly his specific issue orientation and those of other “muckrakers” cut across the philosophical eccentricities of nearly everyone and that means that there could be some progress and hope for improvement of social problems. Not a glorious second coming which I hope to see springing whole-hog out of the Woodstock Nation, but a society a little more humane, a little fairer.

I asked him whether he thought things have been getting better or worse for the average person over the last 500, 50, or 10 years, and what about the future?

“I’d have to say that things have gotten much better. Life expectancy is way up, and of course, workers have the right to trade unions. They work fewer hours and the jobs are less dangerous, but at the same time we’ve had the Bomb, and Auschwitz, My Lai, and a terrible rate of heroin addiction here in New York. Th

“I am a pessimist. Camus writes about Sisyphus accepting the burden placed upon him to hopelessly push a large rock up a mountain only to see it fall back down, over and over again. In his hopelessness he is satisfied to accept the process of struggle as his own way, the best choice in an absurd universe.”

Newfield, seeing a troubled world and knowing there is no one great answer to the diverse problems, expects no great change for the better, or for the worse. He feels the responsibility to do his share, seeing himself in a privileged position as a journalist, to helping pick away at the unending mountain of human distress. Unlike most of us who are content to “slouch towards Bethlehem,” we’ve learned the absurdity of trying to make sensible change, and have therefore given up, Newfield believes, in the words of Bobby Kennedy:

“One person can make a difference.” And so he does.

“Do you still like sports?”

“Yeah, I’m crazy about the Knicks.”

“Who do you like most?”

“De Busschere.”

“Why?”

“I like his attitude.”

“How would you characterise it?”

“Determined.”